For 20 years, Dhoni Tokbe saw fluoride-contaminated water cripple fellow villagers in his village of Sarek Teron in Assam’s Karbi Anglong district. Affecting the young and old alike, the water has caused teeth loss, twisted ankles, and misshapen legs among villagers. The situation is similar in many other villages of Karbi Anglong. As per reports, despite several government initiatives, the water condition remains the same.

When village leaders called Dhoni and others for a meeting concerning drinking water, he was unsure. He wondered if this was just like any other meeting or a meeting that could provide a sustainable solution to their water woes. His concerns were valid. But as the meeting progressed his uncertainty was replaced with gratitude. Delighted with the meeting’s progress and its offering, Dhoni was hopeful that his village could now be surely saved from fluoride-contaminated water. “Thank you! Our children will be saved,” he said at the end of the meeting.

The Re 1 filter

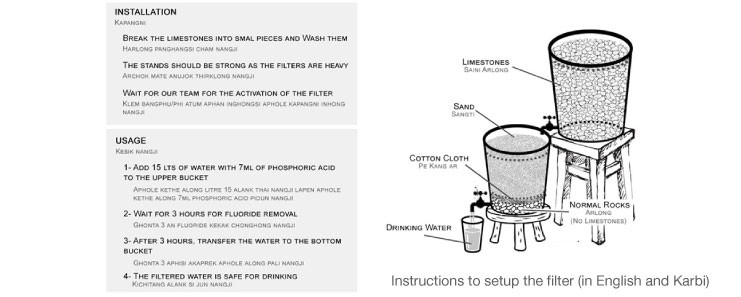

The reason for Dhoni’s happiness was the meeting’s proposed solution to the region’s water problem: a DIY (Do-It-Yourself) fluoride water filter. Dhoni and the rest of the villagers learned how they could install the filter themselves. All they had to do was collect the material of the filter which included two buckets, limestone, and dilute phosphoric acid from a nearby village for free and follow the instructions.

Dhoni’s family was one of the 1,680 families in Karbi Anglong The Art of Living reached out to as part of a pilot fluoride-free water project.

A patent of Professor Robin Dutta of Tezpur University, the filter called Fluoride Nilogon has a royalty fee of Re 1. However, the material of the filter amounts to nearly a thousand rupees. "This cost was borne by the Department of Public Health Engineering Department, Karbi Anglong Autonomous Council (KAAC)," says Vishnu Prakash, project coordinator from The Art of Living.

From Paraguay to Karbi Anglong

Raul Alvarez, an analyst from Paraguay had never thought that he’d travel to help people get clean drinking water in India’s remote villages. However, while volunteering at The Art of Living International Center, Bengaluru, he got the chance to do just that.

Excited, he along with three other volunteers from Argentina, packed their bags to reach Diphu - headquarter of Karbi Anglong. The four of them along with local project volunteers decided on a strategy to reach villagers with the DIY filters.

Armed with a translator on most occasions, they began conducting village meetings where they told villagers about the filter - how it could solve the water problem, its working and the way to install it.

With the help of local volunteers, the team conducted meetings in 17 villages. Followed by them inviting 1,680 families to collect the filter’s raw material from a central point.

The team thought it was important for the villagers to collect the filter material and set it up themselves. “We wanted them to value what they are getting. This model of distribution ensured that villagers are more involved,” shares Raul.

Meanwhile, the project team started preparing the material: diluting phosphoric acid, receiving truckloads of limestone, crushing them, inserting taps into buckets and so forth. Hundreds of villagers started pouring in every alternate day to receive the material and a leaflet of instructions to set up the filter.

Bringing the filter to use

Now, the team had a challenging task ahead of them. “We now had to go to every home and check if they had set up the filter right and activate it with a certain measure of phosphoric acid,” says Vishnu Prakash, project coordinator.

Battling tough terrain, the team went to every home. But most villagers were occupied with the annual paddy season. “When we visited homes, the villagers were busy on the farm and were not there in their homes,” shares Raul.

So, the team changed their visiting hours. Instead of visiting in the afternoon or late morning, the team visited homes during early morning hours. That way, they could meet the villagers.

However, the next challenge was that many had either set-up the filter incorrectly or had not set it up at all. “Some were using the bucket to store their ration. Some had put the limestone in the sand. Some did not get the time to wash the limestone. There were also some who had set up the filter correctly and were just waiting for us to activate it,” says Kamalsing Ingte, a local volunteer.

In every defaulter’s case, the team helped set-up the filter. But due to a large number of homes, the team of five was visiting, keeping a track of homes that had received assistance was difficult.

“So we used a ribbon system - one ribbon strung on the door of a house meant one of us had visited the home once. Two ribbons meant the filter has been set up. And three ribbons meant the filter had been activated,” says Raul.

Despite the ribbon system, it was still difficult to reach all homes. So the project ensured 1,400 families set-up and used the fluoride filter against the 1,680 families it reached out to initially. Under this pilot project, community filters in ten schools were also installed.

Now the vision of the project is only growing.

“In the next two phases of the project, we will reach out to 5,000 families with the DIY filters and 40 schools with community filters,” says Kamal.

If you want to partner with us and help more families in Karbi Anglong get access to fluoride-free water, write to us at info@projects.artofliving.org

Written by Vanditaa Kothari